|

|

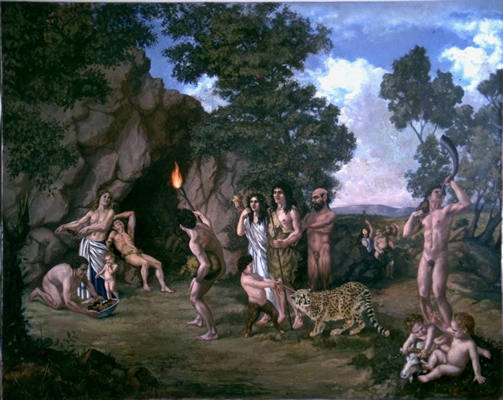

The Return of Dionysus

|

His Character and Functions. - Dionysus is etymologically the ‘ Zeus of Nysa’ and seems, by several similarities of legend and function, to be the Greek form of the Vedic god Soma. The cradle of his cult was Thrace. It was brought to Boeotia by Thracian tribes, who established themselves in that country, and was afterwards introduced to the island of Naxos by Boeotian colonists. The cult of Dionysus spread throughout the islands, whence it returned to continental Greece, first to Attica, then later to the Pedoponnese.

The figure of the primitive Dionysus is complicated by traits borrowed from other and foreign gods, notably the Cretan god Zagreus, the Phrygian god Sabazius, and widened as his character became enriched with fresh contributions. In origin Dionysus was simply the god of wine; afterwards he became god of vegetation and warm moisture; then he appeared as the god of pleasures and conceptions, as a king or supreme god.

Cult and Representations. - Dionysus was honoured throughout Greece; but the character of the festivals which were dedicated to him varied with regions and epochs.

One of the most ancient festivals was that of the Agriomia, first celebrated in Boeotia, especially at Orchomenus: the Bacchantes immolated a young boy. Human sacrifice was also practised at Chios and at Lesbos; it was rural Dionysia: in December the Lenaea, festival of the wine press, when the god was offered the new wine; at the end of February the Anthesteria, floral festivals which lasted three days, during which wine of the last vintage was tasted. In the sanctuary of Lenoeon there was procession followed by a sacrifice offered by the wife of the archonking, and finally boiled seed was offered to Dionysus and Hermes. The most brilliant festivals were the Greater Dionysia, or urban Dionysia, at the beginning of March. It was during these festivals that dramatic representations were given. In addition to those dignified ceremonies all Greece celebrated festivals of orgiastic character as well, such as those which took place on the slopes of Mount Cithaeron.

The appearance of Dionysus altered at the same time as his legend. He was first depicted as a bearded man, of mature age, with brow generally crowned with ivy. Later he appears as a beardless youth of rather effeminate aspect. Sometimes the delicate nudity of his adolescent half-covered body by the nebris, a skin of a panther or fawn; sometimes he wears a long robe such as women wore. His head with its long curly hair is crowned with vine leaves and bunches of grapes. In one hand he holds the thusus, and in the other, grapes or a wine cup.

The Birth and Childhood of Dionysus. - When the earth has been made fertile by life-giving rains it must, in order that its products may reach maturity, endure the bite of the sun which burns and dries it up. Only then do its fruits develop and the golden grapes appear on the knotty vine. This seems to be the meaning of the myth of Semele who was normally considered to be the mother of Dionysus.

|

Semele, daughter of Cadmus, King of Thebes, was seen by Zeus and yielded to him. Zeus would come to her father’s palace to visit her. One day, at the suggestion of the treacherous Hera who had assumed the guise of her nurse, Semele begged Zeus to show himself to her in his Olympian majesty. She was unable to endure the dazzling brilliance of her divine lover and consumed by the flames which emanated from Zues’ person. The child she carried in her womb would also have perished had not a thick shoot of ivy suddenly wound around the columns of the palace and made a green screen between the unborn babe and the celestial fire. Zeus gathered up the infant and, as it was not yet ready to be born, enclosed it in his own thigh. When the time was come he drew it forth again, with the aid of Ilithya, and it is to the double birth that Dionysus owed the title Dithyrambos.

Zeus confided his son to Ino, sister of Semele, who lived at Orchomenus with her husband Athamas.

Such was the commonest version of the story. It was also related that Cadmus, learning of the guilty liaison of his daughter Semele, had her shut up in a chest and thrown into the sea. The chest was carried by the waves as afar as the shores of Prasiac in the Peloponnese; when it was opened Semele was dead, but the child was still alive. He was cared for Ino.

Hera’s jealous vengeance was unappeased and she struck Ino and Athamas with madness. Zeus succeeded in saving his child for the second time by changing him into a kid whom he ordered Hermes to deliver into the hands of the nymphs of Nysa.

Where was Nysa? Was it a mountain in Thrace? One seeks its precise situation in vain; for every region where the cult of Dionysus was established boasted of having a Nysa.

Dionysus, then, passed his childhood on this fabled mountain, cared for by the nymphs whose zeal was later recompensed; for they were changed into a constellation under the name of the Hyades. The Muses also contributed to the education of Dionysus, as did the Satyrs, the Sileni and the Maenads. In Euboca they said that Dionysus was confided by Hermes to Macris, daughter of Aristacus, who nourished him with honey.

With his head crowned by ivy and laurel the young god wandered the mountains and forests with the nymphs, making the glades echo with his joyful shouts. In the meanwhile old Silenus taught his young mind the meaning of virtue and inspired him with the love of glory. When he had grown up Dionysus discovered the fruit of the vine and the art of making wine from it. Doubtless he drank of the wine without moderation at first, for they said Hera had stricken him with madness. But the disease was short-lived. To cure himself Dionysus went to Dodona to consult the oracle. On the way he came to a marsh which he crossed by mounting an ass. To reward the animal he bestowed on it the gift of speech. When he was cured Dionysus undertook long journeys across the world in order to spread the inestimable gift of wine among mortals. Marvellous adventures marked his passage through the countries he visited.

The Travels of Dionysus. - Coming form the mountains of Thrace he crossed Boeotia and entered Attica. In Attica he was welcomed by the king, Icaraus to whom he presented a vine-stock. Icarus had the imprudence to give his shepherds wine to drink; as they grew intoxicated they thought they were being poisoned and slew him. The daughter of Icarus, Erigone, set out to look for her father and, thanks to her dog Maera, at last discovered his tomb. In despair she hanged herself from a nearby tree. In punishment for this death Dionysus struck the women of Attica with raving Madness. Icarus was carried to the heavens with his daughter and her faithful dog. They were changed into constellations and became the Wagoner, Virgo and the Lesser Dog Star.

In Aetolia Dionysus was received by Oeneus, King of Calydon, and fell in love with Althaca his host’s wife. Oeneus pretended not to notice and the god rewarded his discretion by giving him a vine-stock From the fleeting union of Dionysus and Althaea was born Deianeira.

|

In Laconia Dionysus was the guest of King Dion who had three daughters. Dionysus fell in love with the youngest, Carya. Her two older sisters threatened to expose the affair by warning their father. Dionysus struck them with madness, then changed them into rocks. As for Carya, she was turned into a walnut tree.

After continental Greece Dionysus visited the islands of the Archipelago. It was in the course of this voyage that the god, walking one day by the seashore, was abducted by Tyrrhenian pirates and carried aboard their ship. The took him for the son of a king and expected a rich ransom. They tried to tie him up with heavy cords, but in vain. The knots loosened of their own accord and the bonds fell to the deck. The pilot, terrified, had a presentiment that their captive was divine and attempted to make his companions release him. The pirates refused. Then occurred a series of prodigies. Around the dark ship flowed wine, fragrant and delicious. A vine attached its branches to the sail, while around the mast ivy wound its dark green leaves. The god himself became a lion of fearful aspect. In horror the sailors leapt into the sea and were immediately changed into dolphins. Only the pilot was spared by Dionysus.

On the isle of Naxos Dionysus one day perceived a young woman lying asleep on the shore. It was the daughter of Minos, Ariadne, whom Theseus had brought with him from Crete and just abandoned. When she awoke Ariadne realised that Theseus had left her and gave way to uncontrollable tears. The arrival of Dionysus consoled her and shortly afterwards they were solemnly married. The gods came to the wedding and showered gifts on the couple. Dionysus and Ariadne had three sons: Oenopion, Euanthes and Staphylus. The Homeric tradition has a different version of the Ariadne episode. Ariadne was supposed to have been killed by Artemis and it was only after her death that Dionysus married her. In Naxos they showed the tomb of Ariadne and to her honour two festivals were celebrated: one mournful, bewailing her death; the other joyful, commemorating her marriage to Dionysus.

The travels and adventures of Dionysus were not limited to the Greek world. Accompanied by his retinue of Satyrs and Maenads he went to Phrygia, where Cybele initiated him into her mysteries. At Ephesus in Cappadocia he repulsed the Amazons. In Syria he fought against Damascus who destroyed the vines which the god had planted and was punished by being skinned alive. Then he wen into the Lebanon to pay a visit to Aphrodite and Adonis whose daughter, Beroe, he loved. After having reigned for some time over Caucasian Iberia, Dionysus continued his journey towards the East, crossing the Tigris on a Tiger sent by Zeus, joined the two banks of the Euphrates by a cable made of vine-shoots and ivy-tendrils, and reached India where he spread civilisation. We also find him in Libya where he helped Ammon to reconquer his throne from which he had been deposed by Cronus and the Titans.

After these glorious expeditions Dionysus returned to Greece. He was no longer the rather rustic god recently come down from the mountains of Boeotia. His contact with Asia had made him soft and effeminate: he now appeared in the guise of a graceful adolescent, dressed in a long robe in the Lydian fashion. His cult became complicated by orgiastic rites borrowed from Phrygia. Thus he was received in Greece with distrust, sometimes even with hostility.

When he returned to Thrace, notably, the king of the country, Lycurgus, declared against him. Dionysus was obliged to flee and seek refuge with Thetis, in the depths of the sea. Meanwhile, Lycurgus imprisoned the Bacchantes who followed the god, and Dionysus struck the country with sterility, depriving Lycurgus of his reason. In his madness Lycurgus killed his own son, Dryas, whom he mistook for a vine-stock. The desolation of Thrace did not cease until the oracle ordered that Lycurgus be conducted to Mount Pangaeum where he was trampled to death under the hooves of wild horses.

Dionysus was no better received by Pentheus, King of Thebes, who threw the god into prison. Dionysus escaped without trouble and struck Agave, the mother of Pentheus, as well as the other women of Thebes, with madness. They were transformed into Maenads and rushed to Mount Cithaeron where they held Dionysian orgies. Pentheus had the imprudence to follow them and was torn to pieces by his own mother. This terrible drama forms the subject of Euripides’ Bacchae.

|

A similar tragedy overtook the inhabitants of Argos who had also refused to recognise the divinity of Dionysus: the women, driven out of their minds, tore up and devoured their own children.

Among the chastisements which Dionysus inflicted, one of the most famous concerned the daughters of Minyas, King of Orchomenus. They were three sisters: Alcithoe, Leucippe and Arsippe. Since they refused to take part in the festivals of Dionysus, he visited them in the guise of a young maiden and tried to persuade them by gentleness. Being unsuccessful, he turned himself successively into a butt, a lion and a panther. Terrified by these prodigies, the daughters of Minyas lost their reason and one of them, Leucippe, tore her son Hippasus to pieces with her own hands. Finally they underwent metamorphosis: the first became a mouse, the second a screech-owl, the third an owl.

Thenceforth no one any longer dreamed of denying the divinity of Dionysus or of rejecting his cult.

The god crowned his exploits by descending into the infernal regions in search of his mother, Semele. He renamed her Thyone and brought her with him to Olympus among the Immortals. At Troezen, in the temple of Artemis Soteira, they showed the exact place where Dionysus had returned from his subterranean expedition. According to the tradition of Argos the route to the underworld had been shown to the god by a citizen of Argos, one Polymnus, and Dionysus had come up again via the sea of Alcyon.

On Olympus Dionysus took part in the struggle against the Giants; the braying of the ass on which he rode terrified the Giants and Dionysus killed Eurytus or Rhatos with his tarysus.

Foreign Divinities Assimilated by Dionysus. - The exuberance of the legends of Dionysus is explained not only by his great popularity but also because the personality of Dionysus absorbed, as we have already said, that of several foreign gods, notably the Phrugian Sabazious, the Lydian Bassareus and the Cretan Zagreus.

Sabazius, who was venerated as the supreme god in the Thracian Hellespont, was a solar-divinity of Phrygian origin. Traditions concerning him were very diverse. Sometimes he was the son of Cronus, sometimes of Cybele whose companion he became. His wife was either the moon-goddess Bendis or Cotys (of Cottyto), and earth-goddess analogous to the Phrygian Cybele. Sabazious was represented with horns and his emblem was the serpent. The Sabazia were celebrated in his honour nocturnal festivals orgiastic character.

|

When Sabazius was later assimilated by Dionysus their legends became amalgamated. Some said that Sabazius had kept Dionysus enclosed in his thigh before confiding him to the nymph Hippa; others claimed on the contrary that Sabazius was the son of Dionysus. It was finally supposed to have come from the Thracian Hellespont.

Sometimes the Bacchantes were called Bassarids and Dionysus himself had the epithet Bassareus, in which case he was represented wearing a long robe in the Oriental fashion. The lexicographer Hesychius considered this to be a reference to the fox-skins which the Bacchantes wore; but it would rather seem to be an allusion to an Oriental divinity absorbed by Dionysus. Indeed, in Lydia a god similar to the Phrygian Sabazius was venerated. The place of his cult was Mount Timolus where, according to Orphic-Thracian legend, Sabazius delivered the infant Dionysus to Hippa. Timolus actually became one of the favourite haunts of Dionysus. What was the name of the Lydian god? It has been conjectured that his name was Bassareus. He was doubtless a conquering god and to him may be attributed the origin of Dionysus’ distant conquests. Bassareus could also explain the visit of Dionysus to Aphrodite and Adonis, and perhaps also the legend of Ampelus, a youth of rare beauty whom Dionysus cherished with particular affection. One day when he was attempting to master a wild bull Ampelus was tossed and killed by the animal. Dionysus was heartbroken and obtained the permission of the gods to change Ampelus into a vine.

The identification of Dionysus with the Cretan god, Zagreus, who was very probably in origin the equivalent of the Hellenic Zeus, introduced - under the influence of Orphic mysticism - a new element into the legend of the god, that of the Passion of Dionysus.

This is what they said of Dionysus-Zagreus: He was the son of Zeus and Demeter - or of Kore. The other gods were jealous of him and resolved to slay him. He was torn into pieces by the Titans who threw the remains of his body into a cauldron. Pallas Athene, however, was able to rescue the god’s heart. She took it at once to Zeus who struck the Titans with thunderbolts and, with the still beating heart, created Dionysus. As for Zagreus, whose remains had been buried at the foot of Parnassus, he became an underworld divinity who in Hades welcomed the souls of the dead and helped with their purification.

On these sufferings and resurrection the adepts of Orphism conferred a mystic sense, and the character of Dionysus underwent profound modification. He was no longer the rustic god of wine and jollity, formerly come down the mountains of Thrace; he was no longer even the god of orgiastic delirium, come from the Orient. Henceforth Dionysus - in Plutarch’s words - ‘the god who is destroyed, who disappears, who relinquishes life and then is born again, became the symbol of everlasting life.

Thus it is not surprising to see Dionysus associated with Demeter and Kore in the Eleusinian mysteries. For he, too, represented one of the great life-bringing forces of the world.

The retinue of

Dionysus rural divinities. From early

times in Greece the vintage festivals were occasions for joyful processions

in which priests and the faithful, men and women, of the cult of Dionysus

took part. These were called Bacchants and Bacchantes or Maenads. It was the

habit to provide the god with a cortege of thiasus composed of secondary divinities

more or less closely bound up with his cult: Satyrs, Sileni, Pans, Priapi,

Centaurs, Nymphs.

Source:

Larousse, Enclycopedia of Mythology. Paul Hamlyn Limited, London, 1959